FOUR WALKS

By Sonia Fernández Pan

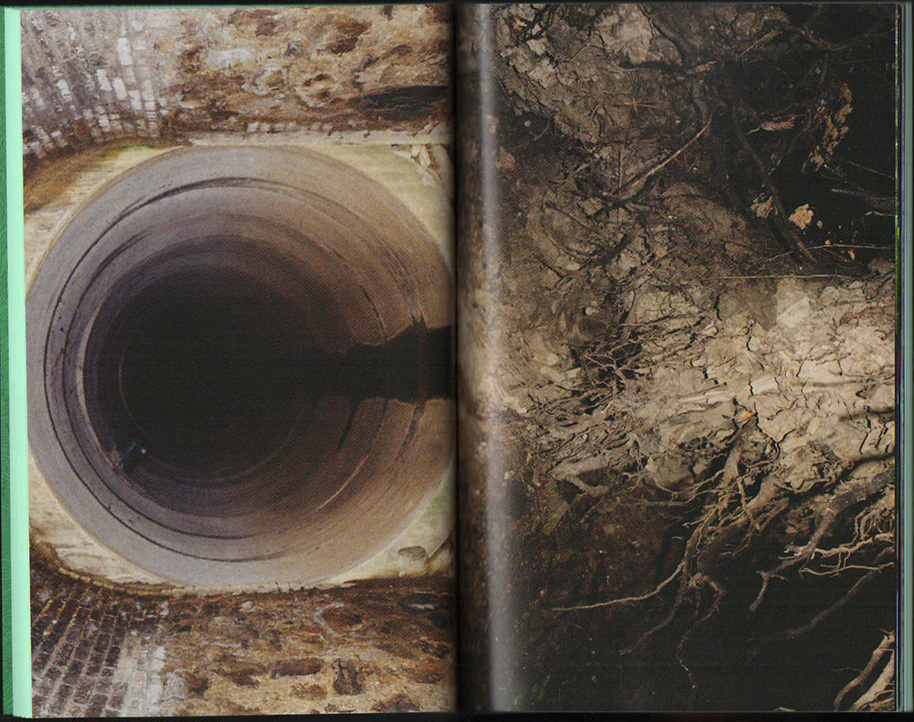

Scan of the book Four Walks, walk-performance Intravia. Left: Photograph of a tunnel under "Revolt de les monges" in Collserola (Barcelona) by Mirari Echávarri. Right: Roots of a fallen tree in Collserola by Gerard Ortín Castellví.

Scan of the book Four Walks, walk-performance Intravia. Left: Photograph of a tunnel under "Revolt de les monges" in Collserola (Barcelona) by Mirari Echávarri. Right: Roots of a fallen tree in Collserola by Gerard Ortín Castellví.

“The human being is artificial by nature” is a sentence I came across in my adolescence. I remember writing it on a piece of paper as a strategy to make the idea last longer. To write is, among other things, to provide thought with material support. But if I still remember the sentence, it's not so much for that reason as for the predicament presented by a phrase in which two concepts in crisis merge: nature and its supposed antagonist, the artificial. And in which they do so, furthermore, trying to distort their usual meanings. The sentence emerged in a specific situation: observing the material constitution of a street and deciding that everything constructed by human beings was as natural as could be the woods or the mountains. That our habitat was a geometry of concrete and that maybe the artificial referred more to a combination and assemblage of materials and shapes than to an essence of things. Perspective view. But my adolescent revelation was not such, it was rather the confirmation of the meaning the dictionary already assigns to the word artificial: made by humans.

But if this sentence is problematic as of today, it's not so much for its emphasis on the artificial as one of the characteristics of the human being – we're more and more conscious that our perception and understanding of the world is based on cultural constructs – but rather for the deliberate use of the expression “by nature”. Especially now that many affirm that nature doesn't exist or that we need to begin to do away with a concept that works to split the world into two distinct parts. Nature versus culture or society. The savage opposed to the domestic. The conceptual challenge that nature poses makes it one of the most complex words in the language. Its meaning is so unstable that it doesn't lead us anywhere concrete if we don't add to it more ordinary signifiers to help us understand what we're talking about when we talk about nature. It contains too many things inside it: from tsunamis to gender, via atoms, social norms, viruses, climate change, love, species extinction, tectonic movements or even markets. Nature is also an ideological form that refers to a basic state prior to our existence, an aspirational place to which to escape from the evils that lie in wait for the world. Our world. As if the world didn't form part of a larger system of human and non-human relations that transcend us. As if we weren't part of that infinite collections of things in constant interaction and hybridization that we call world. We live in an unstable state halfway between nature and culture. And even though both terms are obsolete, we're incapable of ridding ourselves of them to understand where we are. Antropocene is not enough. Rejecting a notion continues to put it forward. Getting rid of it means eliminating it from our vocabulary.

Being primarily in the hands of scientists, nature has, for a long time, been the domain of science . They have been responsible for two opposing interpretations which, however, share the presumption of a distinct internal logic: that of order and chaos. The stable settling of the world after a tumultuous beginning in which the human intervenes in an irresponsible way in the stable development of nature, against its immanent catastrophic turbulence, which is perhaps more attractive because it makes us less responsible for our actions within it. Both conceptions deny the possibility that the world is a historical and relational construct in constant movement. They also overlook the plural condition of nature. That there isn't one, but many, product of the diverse and continuous rearrangements of which we form part. That the world is not: it becomes. Defining nature means searching for an essence. It's an ontological exercise within a double bind: that of nature as a concept and of ontology as a method of knowing.

Haga Park suring the walk-performance Haga–DK51 (Stockholm). Photograph by Gerard Ortín Castelví

Haga Park suring the walk-performance Haga–DK51 (Stockholm). Photograph by Gerard Ortín Castelví

For years now, thinking about nature has no longer been the sole domain of science. Nor of philosophers, though these days they present themselves as its new spokespeople. They are the necessary doubt before indisputable scientific truth. But both disciplines rely on discourse, prolonging the endless dialectical combat between philosophy and science. A socially accepted binary situation, just like the one between nature and culture. An interaction that constructs a paradigm from its constant repetition. The discourse on nature as another of the so many resources it offers us. But it's also possible to think about nature from another place: from the place of artistic practice, relegating the word to second place to the benefit of direct experience and other modes of language which include the material and animistic dimension of the surroundings and of (artistic) objects.

In 2012, I participated in Gerard Ortín's Intravía. At that time, the idea of nature didn't seem as problematic to me as it does now. Being conscious of something doesn't always mean acting accordingly. Besides, I remember that in the beginning, one of the immediate appeals of Intravía was that it “took place in nature”. And that, furthermore, it happened outside the usual timetable of art. Artistic practice as a possibility of escape from two routines: his and ours. Intravía entailed a nocturnal group experience with a strong ritual component, through the Collserola woods. It began with a protocol which required us, after ingesting a brew, to be silent during the walk. Silence, which doesn't usually hold when a group of people get together, opened an access road to introspection of the walk and worked as a connection between us all, transforming us into a single unpredictable object inside a territory. The collective human body as one more object among many other objects, spanning from that elusive nature, to a whole series of non-human actors inside a territory previously edited by Gerard Ortín and his team of collaborators. In group dynamics, language tends to separate us into smaller groups by means of separate conversations. Silence began as a rule only to become, after a few minutes, a voluntary gesture. Our silence permitted us to pay more attention to the acoustic dimension of the environment and of our contact with it. If there was an internal division in Intravía, it was produced from the functionality of an object: a flashlight that some of us were holding to light up the walk for the rest of the participants. The walk included a route through the woods; a rest stop with lit-up images of that very territory, showing fragments of it that the lack of light wouldn't allow us to see otherwise; a second path through the woods towards the motorway; a waste-pipe big enough to hold us inside and serve as a concert hall with artificially reproduced sounds of nature, until we arrived to an area with several parked cars which emitted “white noise” at a considerably high volume. The animistic force of technology and the adjournment of the walk. When we believed that Intravía had reached its end, and split off into small groups in several cars to return to our meeting point to take the train to return to Barcelona, a final unexpected element emerged: a song that played during the car journey and which contributed to prolonging our silence further. At least it did for me, as returning to Barcelona had something traumatic about it. Most probably Intravía didn't consider in its script this return to the city and the emotional shock produced by the change in surroundings. Between Collserola train station and Plaça Catalunya, barely a few minutes passed. Between Intravía and my everyday perception of the city, several hours had to pass. If Intravía was a story of fiction-experience, I felt like a character who had involuntarily left the story prematurely. Like a stalker that the Zone punishes, not with severe wounds to the body, but with the desire to enter it again right away, without knowing how to.

Sonic intervention White Noise Car Parade by Jaume Ferrete Vázquez for the walk-performance Intravía (2012 & 1014). Photograph by Marc Vives.

Sonic intervention White Noise Car Parade by Jaume Ferrete Vázquez for the walk-performance Intravía (2012 & 1014). Photograph by Marc Vives.A few days later, I enthusiastically recounted the experience over the phone to my father. When I finished, he asked me the following: “you've had to go through art to be moved by nature?” Considering that many weekends of my childhood took place in a remote little village in Galicia, and that I always went grudgingly, my father's reaction is no surprise. In more recent conversations with him, he's told me about his inability to appreciate or be moved by nature. For my father, it's intrinsically linked to work in the fields and void of the bucolic or contemplative character it has been socially attributed with. He's incapable of experiencing the landscape in the same way as do those who haven't grown up conditioned by a direct relation of labour with the rural environment. The landscape doesn't exist beyond human vision: it is a domesticating and representational form of the surroundings. A protective barrier between us and nature, reconverted into transcendental entity and promise. This way of understanding nature as a means for human survival -and a daily sacrifice- shows that such a line between nature and humans doesn't exist. That there's neither an outside nor an inside. It is also a lesser proof of the extractivist attitude of human beings with respect to the world they live in . That our relationship with the environment is based on a situation of dependency is not sufficient reason for the type of relation we exercise towards it.

My enthusiasm didn't come so much from having spent several hours in Collserola at night, but from what took place there. A group experience in silence and through movement; participation in an exploratory ritual provided by a script, which became clearer as we progressed; the confusion between the obstacle and the stimulus; artistic intervention in a wood; the editing of a territory; the creation of a fiction beyond language. The conscious production of an assemblage of human and non-human elements which could demonstrate, through practice, that hybrid and plural nature which some of those philosophers talk about in their texts. A different idea of what we understand as nature, through the body rather than discourse . The confirmation of nature as a mise-en-scène but also the negation of the landscape. The impossibility of distancing ourselves from the medium despite a contemplative and expectant attitude towards it. The prolonged bewilderment subsequent to the experience and the nostalgic confirmation of the unique character of every event.

Intravía was the first of a series of walk-performances that have taken place in different parts of Europe. If there's something that distinguishes this one from the others, it's Gerard's personal and prolonged relationship with the territory in which it took place, Collserola. In Intravía the role of explorer of new worlds that appears in so many sci-fi novels may have been easier for a lot of us to get into than for him. As often happens with those who have been born and raised in a rural environment, I wonder if Gerard also perceives nature in a more or less permanent way, as a potential space of labour. Or as a place that's impossible to escape to because it's not possible to escape from. I read somewhere that art is an eminently urban product, even though it doesn't always take place in cities. That might explain my father's question. The need for an urban mentality to be capable of letting ourselves be affectively moved by a non-urban environment. Or the need for an artistic habit to let ourselves be affected by all that doesn't take place in a white cube or its usual satellites. In fact, Intravía was defined as an offsite project by the institutional framework that contributed to its production. A category that is problematic because it leads us to believe that art has its own place, even “natural place”. And any way out of it, refers directly back to it through its absence.

While we also walk inside exhibition spaces, it's undeniable that, as spectators, our feet aren't the part of the body we privilege there. We're not even conscious of the slow and subtle movements we make, trying to pass unnoticed between other people and things. We become an eye, forgetting that we have a body with many more active parts and functions. Turning walking into artistic practice, and, consequently, an aesthetic experience, returns to us a moving body which has been absent in art for so long. The role of the audience also participates in this cliché that associates intellectual activity with a static position. The history of thought seems to rely solely on a table and chair. And not so much because those who have dedicated themselves to thinking about the world always arrived at their conclusions whilst seated, rather because that's how we tend to imagine them. That common place which assumes that for the mind to move it's necessary for the body to stop, is false. We only have to get walking to realise that. Thinking is a physical activity. And if that weren't enough, Philosopher's Walk in Heilderberg, Germany, functions as historic proof against that so largely extended view that in order to think the body must stop. Sure, writing is something we do sitting. At least for the moment. But writing and walking are two actions more similar than they appear. Writing provokes a path towards the construction of an account which is yet to appear. Walking produces a path which constructs a territory that exists prior to us. In writing, stopping is usually associated with a state of being lost or disoriented. The text doesn't tell us where to go. When walking, stopping can also be a symptom of being lost. Of having doubts about the direction we've taken. However, stopping here allows the production of the landscape. A stable framework for something that keeps moving. A return to the eye of the exhibition room. Walking is an exercise in writing the territory with our bodies.

Diemer Vijfhoek or PEN-island (Diemen, The Netherlands) the artificial pentagonal peninsular where the walk-performance Vijfhoek took place. Photograph by Paul Paris. Courtesy of Archive Beeldbank Historische Kring Diemen.

Diemer Vijfhoek or PEN-island (Diemen, The Netherlands) the artificial pentagonal peninsular where the walk-performance Vijfhoek took place. Photograph by Paul Paris. Courtesy of Archive Beeldbank Historische Kring Diemen. Vijfhoek, Trabeska and Haga—DK51 send me back to the Strugatski brothers' Zone. Vijfhoek has something of a post-apocalyptic landscape. And in writing landscape, I realise that even the end of the world as we know it is conceived from a contemplative attitude. It must be for that reason that one of the characters in the sci-fi novel, El fondo del cielo by Rodrigo Fresán, wonders what the point is of an apocalypse without spectators. In Roadside Picnic there's no catastrophe. The Zone, which exists in the suburbs of a fictional city in Canada, could simply be the product of an ephemeral contact between a group of extraterrestrials and our planet. A place which behaves in a strange and unpredictable way as a result of the items left behind by some extraterrestrials after a stopover on their way to space. A picnic with more consequences than others. The roadside stop of these unknown beings produces a hybrid nature populated by objects which, for the inhabitants of Harmon, have a value that they don't have for the unknown beings. No text of new materialism has dealt so generously with the agency of trash and its commercial standing in the economy. The stalkers are a direct product of the passion aroused by the buying and selling of these alien artifacts. But their activity is simply one more type of hidden economy.

Like the Zone, Diemer Vijfhoek is an inhospitable territory for humans. A field of nettles extending over the pentagonal peninsula in Diemen, east of Amsterdam, it was created in the 70s to protect an electricity plant which supplied the majority of the city, and its surroundings were used as a chemical dumping ground. A form of hybrid nature that seems to want to protect itself from those who created it. Direct contact between the human body and the nettles produces an allergic reaction. In order to avoid the possible consequences of this contact, each of the participants in Vijfhoek was given a special plastic suit. According to popular belief there's another way to protect yourself from the sting of the nettles: holding your breath. Make them believe you're inert matter. That you don't have pores they can penetrate. The participants were also given a nettle brew before they began the walk, like receiving a vaccine. Ingesting in small quantities that which we are protecting ourselves from. Immunity in the pathogen itself. Everything outside the suit is toxic, you're safe. Everything outside the suit is safe, you're toxic. The bidirectional character of danger. The predator that never ceases to be prey.

Nettle field nside the Diemer Vijfhoek and Participant during the performance Vijfhoek (2015). Photographs by Gerard Ortín Castellví

Nettle field nside the Diemer Vijfhoek and Participant during the performance Vijfhoek (2015). Photographs by Gerard Ortín Castellví

The method of exploration for Vijfhoek was a transect . Moving forward over the territory in a straight line. Integrating the potential obstacles along the route instead of avoiding them. The human obsession with geometry: a pentagonal peninsular crossed by a straight line that gets produced along the way by virtue of the impact of the body on the ground. To experience a place is to alter it, leave traces. Protecting oneself from the toxic character of nature with a material which also covers this area in some of its strata. The ambiguous condition of plastic in the world: protecting the form with a contaminant matter. Exit the peninsular and walk towards a mall. The preeminent place of zombie capitalism. From the toxicity of nature to the toxic nature of the system. In contrast to the stalkers, the participants of Vijfhoek don't return with strange objects that certify their foray into the Zone or which economically compensate their exposure to imminent danger. In any case, they've been part of an invisible object that leaves traces: the walk.

Chemichal Dump in Deemerzeedijk. Photograph by Paul Paris. Courtesy of Archive Beeldbank Historische Kring Diemen.

The tension between the map and the experience was also present in Trabeska, a straight-line route demonstrating once again that territory is something produced, not something that is already there, permanently, waiting to be found. The map is the fiction of a territory without bodies. A representation which conceals the process of its creation. That excludes the bodies that enable it. It is also the result of the tension between nature and culture. A way to dominate the world through exploration and representation. A product of colonization. Furthermore, Trabeska offered another mode of conflict between nature and culture by means of human action on the territory. A space that is both quarry and cave. The territory as a means of work and as a scientific object. The extraction of materials against the extraction of information. Industrial production against the production of knowledge. And aesthetic intervention as a connection between both spaces. Making the quarry appear inside the cave using sound. Filtering the space through time. Reaching a peaceful coexistence between mutually exclusive situations. The possibility of producing a contact zone between two conflicting realities. And the function of the artist as a connector of worlds.

Photographs from the walk-eprformance Trabeska (2015): Viaduct of the High-Speed Railway and joining of the "Basque Y" infrastructure at San Bizente (Besaide); Participants crossing a forest, doing a transect parallel to the train tracks; Sound installation at Kobaundi.

Photographs from the walk-eprformance Trabeska (2015): Viaduct of the High-Speed Railway and joining of the "Basque Y" infrastructure at San Bizente (Besaide); Participants crossing a forest, doing a transect parallel to the train tracks; Sound installation at Kobaundi.

Haga—DK51 is a several-hours walk through Stockholm, which begins in the biggest park in the city and ends in a subterranean chamber in which the first Swedish nuclear reactor was housed. Between Haga and DK51, the occupation of space through a script. Both places share a story: the progressive domination of nature by man. From the potential arcadia that each garden features, to the potential apocalypse implicit in each nuclear plant. The perversion of the garden is that it makes us believe that a hygienic nature is possible

. It is the human materialization of an ideal of order and harmony. A work of engineering that hides the infrastructure that sustains it. Immune from danger, nature becomes a space of leisure, a subtle form of work that turns us into consumers of the landscape. The nuclear compound, on the other hand, reminds us of the death drive implicit in human progress. After the geological mutation of the planet signaled by the Athropocene, total annihilation. And the contradiction of a socioeconomic system that progresses towards our own eradication. The Zone once again: the nuclear reactor chamber as the final destination of the walk. The room which contains the Golden Sphere, the most sought-after object by the stalkers. Able to grant wishes we didn't even know we had.

We associate a route with horizontality. Walking from one point to another over a surface. When the territory has been intervened in by human action through the rationality of a map, we can allow ourselves not to think of it. It's predictable. We can anticipate it. Haga—DK51 was, on the contrary, a route which ended with the participants' vertical descent towards the nuclear reactor chamber which had been intervened in acoustically and with light. A journey to the depth of earth through which to go back to the past, not from archaeological stratum but through sound. Sound as the least invasive tactic to alter and occupy a space. An exercise in appropriation that doesn't leave a trace. A memory reactor. The acoustic materialization of the past in the present.

Images about the walk-performance Haga–DK51: Dismantling of the R1, first nuclear reactor in Sweden, 1970. KTH, Royal Institute of Technology; Control Room of the R1, 1970, KTH, Royal Institute of Technology. Collapsed ceiling at the basement of R1 Reactor Hall (KTH, Stockholm); Hole where the R1 Nuclear Reactor used to be. A numbered grid was used to measure the levels of radiation of the space after the dismantlement.

Images about the walk-performance Haga–DK51: Dismantling of the R1, first nuclear reactor in Sweden, 1970. KTH, Royal Institute of Technology; Control Room of the R1, 1970, KTH, Royal Institute of Technology. Collapsed ceiling at the basement of R1 Reactor Hall (KTH, Stockholm); Hole where the R1 Nuclear Reactor used to be. A numbered grid was used to measure the levels of radiation of the space after the dismantlement.

The stalkers' exploration of the territory in Roadside Picnic shows how certain surroundings resist being dominated by humans. Walking in the Zone isn't an act of appropriation but of survival. It continually conditions the steps and movements of the stalkers. Its knowledge goes through the body. It imposes obstacles that, once overcome

, give them the incentive to keep going. It's much safer to move in a group. Like any other type of nature, the Zone entails a potential reward: the commercialization of its resources. In its case, strange artifacts; in ours, water, the rest of the species, lithium, petrol, or even the wind. As a territory that resists human understanding, it manages to ensure that the human experience can't develop a method. Strategy is of no use, only tactics. Its rules keep mutating. Hybrid nature manifests its singularity: the laws of physics that usually apply are altered within it. It subjugates those who seek to dominate it. It's a nature in which the concept of nature winds up obsolete. But so too does the idea of the artificial. It's

a supernatural environment, which exceeds the conditions both of nature and

the human. A territory in which the surface occupied is not as important as the experiences produced.

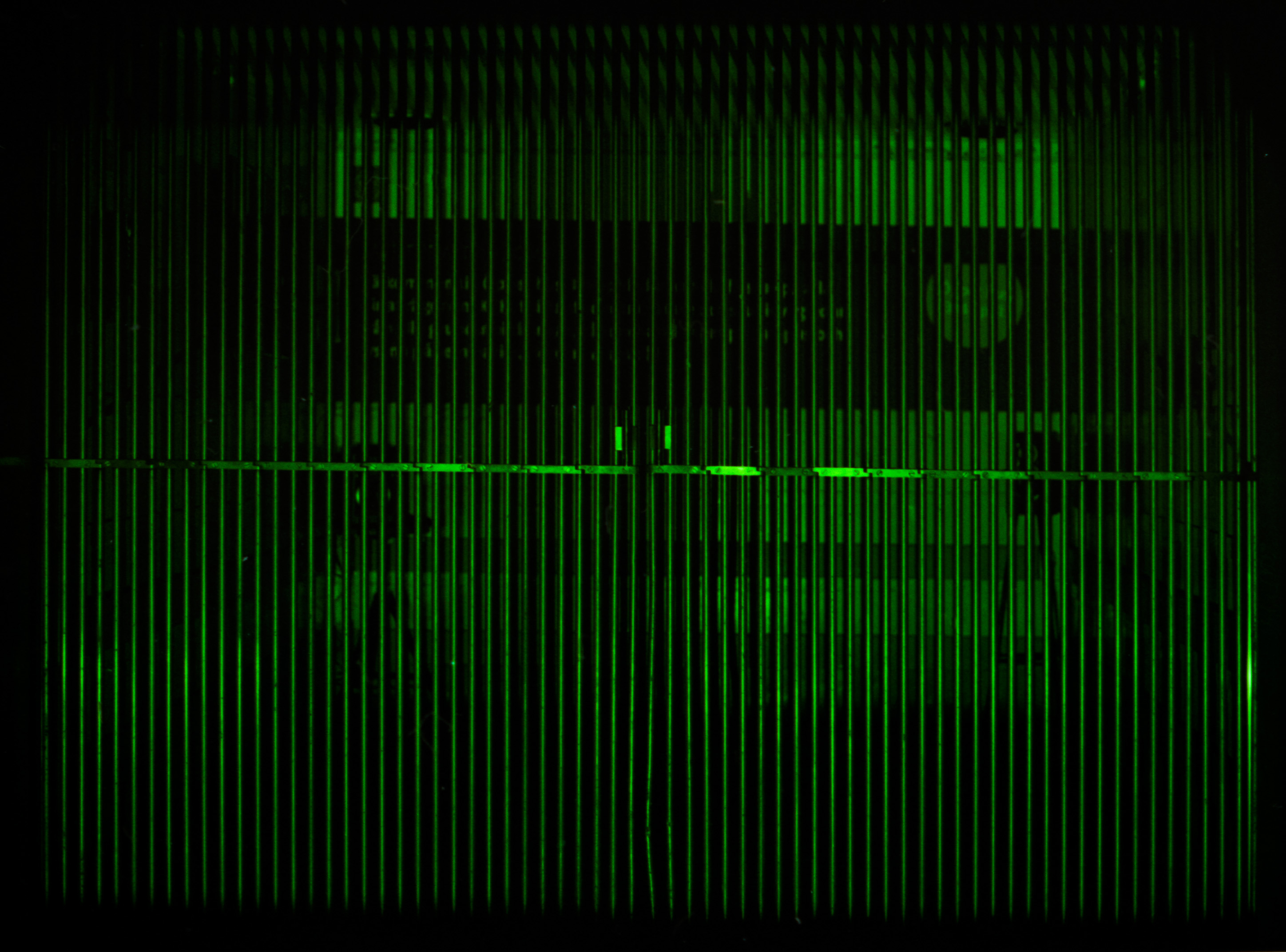

Haga–DK51. Light installation at the elevator of the R1 Reactor Hall. Photograph by Gerard Ortín Castellví.

Haga–DK51. Light installation at the elevator of the R1 Reactor Hall. Photograph by Gerard Ortín Castellví.

🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃🌱🍃

Sonia Fernández Pan is a (in)dependent curator and podcast-maker who researches and writes through art. Author of esnorquel since 2011, a personal project in the form of an online archive with podcasts, texts and written conversations. esnorquel works like a “carrier bag” where the need—and the desire—to think in the company of others is put into practice, as well as emphasizing the importance of oral memory and the collective dimension of story-telling.

Editor of the books A Brief History of the Future and Mirror Becomes a Razor When It’s Broken, she writes irregularly for artists’ projects and other publications. She began curating with F for Fiction, to continue with The Future Won’t Wait, La Capella, Barcelona, 2014–2015; Microphysics of Drawing, Espazo Normal, A Coruña, 2015; Diogenes Without Syndrome, HANGAR, Barcelona, 2015; As if we could scrape the color of the iris and still see, Twin Gallery, Madrid, 2018; we feel untied, but why?, Centro Párraga, Murcia, 2018; and CHRONO-MATTER. Objects are closer than they appear, Efremidis Gallery, Berlin, 2019. She has also been able to develop long-term curatorial projects such as The more we know about them, the stranger they become, Arts Santa Mònica, Barcelona, 2017; and Mirror becomes a razor when it’s broken, CentroCentro, Madrid, 2018–2019. In collaboration with other peers has been part of the projects … at least a provisional way to settle in one place, Azkuna Zentroa & Montehermoso Cultural Center, Bilbao and Vitoria-Gasteiz, 2016–2017; lamusea, 2017; Les escenes. 25 Years after, La Capella, Barcelona, 2019; or Dazwischen, Mies Van der Rohe Pavilion/Sonar Festival, Barcelona, 2019. After years of researching objects and matter as systems of human and non-human interactions, she is currently conducting a co-research on the experience of dance culture and techno music that will lead to an exhibition in late 2020 at La Casa Encendida, Madrid.

A large part of her curatorial and writing practice has been developed in various kitchens and domestic spaces, reclaiming them as interdisciplinary spaces for the production of knowledge. After years in Barcelona, both her kitchen and the current esnorquel headquarters are in Berlin.

🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃 🌱 🍃

This text was first published in 2017 as part of the book Four Walks, edited by Gerard Ortín Castellví. The book revolves around four walk-performances that took place between 2012 and 2016: Intravía (Barcelona, 2012 & 2014), Vijfhoek (Diemen & Amsterdam, 2015), Trabeska (Arrasate-Mondragón, 2015), Haga—DK51 (Stockholm, 2016). It includes another text by Sonia Fernández Pan and photographs by Marc Vives Muñoz, Irati Gorostidi Agirretxe and Mirari Echávarri López. The text has been published on-line in 2020 on the occasion of the project Ecologies of the ghost Landscape at tranzit.sk, curated by Borbála Soós.